| |

|

|

By the time the first space shuttle had been christened

Enterprise in September 1976, Paramount officially green-lighted a Star

Trek movie with a budget of $10 million. Jerry Eisenberg was hired to

produce and Phil Kaufman to direct, with Ken Adam as production designer and

Ralph McQuarrie as production illustrator. The writers for this new film

venture were Chris Bryant and Allan Scott. Their script was titled

Planets of the Titans, and ultimately it, too, was rejected by Paramount.

About this time, the first Star Wars film was released and became an instant

blockbuster. Paramount executives, believing that the motion-picture

audience could support only one major science-fiction franchise, decided

that the tremendous impact of Star War doomed any chance of Star Trek's

succeeding at the box office.

But they also believed there was still value in the

franchise, so on June 10, 1977, Star Trek: Phase II was announced - a

brand-new syndicated Star Trek television series to be produced by

Roddenberry and Harold Livingston. Paramount had planned to make Phase II

the cornerstone of a new, fourth television network, but as the proposed new

network was not coming together as securely as Paramount had hoped, and

plans for it were canceled, Phase II was left a series without a home. At

the same time, 1977's other science-fiction blockbuster, Close Encounters

of the Third Kind, opened to box-office numbers rivaling those of Star

Wars. All at once, Paramount executives saw the error of their ways. Star

Wars had not been a one-time wonder. Determined to tap into the

science-fiction motion picture market with a Star Trek feature, Paramount

quickly made the decision to geen-light Phase II's pilot episode, "In Thy

Image", as a theatrical release, eventually bumping its television budget up

to $15 million, of which almost two-thirds would go to special effects.

To recreate the magic of the original series, Gene

Roddenberry had gathered together those who had made that magic in the first

place. And they did it again. When Star Trek: The Motion Picture premiered

on December 7, 1979, Roddenberry's creation finally transcended the medium

of its creation, ceasing to be a mere television series, at last becoming a

true phenomenon.

The level of detail that can appear on a movie model is far

greater than that which can appear on a model for television. Thus, the

Enterprise built for the unproduced second television series was set aside

and a new model was constructed. The movie Enterprise still followed the

basic updating intially developed by Matthew Jefferies and Joe Jennings, but

new and more detailed modifications were added by a veriety of designers

from Abel & Associates and Magicam.

The final appearance of the new Enterprise interiors

combines the design input of original designer Matthew Jefferies, as well as

Mike Minor, Joe Jennings, movie production designer Harold Michaelson and

director Robert Wise. Control details were developed by Lee Cole, and

control screen readouts by Cole, along with Minor, Rick Sternbach and Jon

Povill. Harold Michaelson was responsible for the design of the attitude

dome on the bridge ceiling, as well as the redesigning of the Enterprise

corridors, which had been built for the second series. Gene Roddenberry had

been unhappy with the new corridors, because he felt they made the

Enterprise look too much like an hotel. Ironically, Michaelson's redesigns

ended up being used in The Next Generation's Enterprise-D, which was

criticized as looking even more like an hotel.

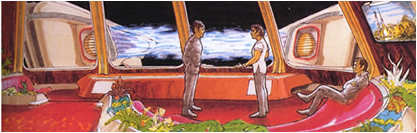

One of Andrew Probert's key concerns was that the sets he

designed would somehow conform to the structure of the starship they were

supposed to exist within. Here we see Probert's development sketches for an

officers' lounge in the saucer section's upper dome, of which an artistic

impression by Probert can be seen above.

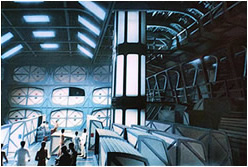

Thoughts on the new Enterprise cargo decks

had already been visualized by

veteran Mike Minor, before Andrew Probert had a chance to address it. The

thinking, then under production designer Harold Michaelson,

was that the cargo bay would be a space 30 feet high that had two walls with

twelve holes containing cargo pods. An impression by Mike

Minor shows additional cargo pods simply stacked or lined up on the deck,

leaving a huge open and unused space above. Furthermore, the walkways along

the sides were rather old-fashioned looking.

The cargo bay scene would be part

live-action and part matte painting. Matte paintings are begun by filming a

plate; a shot of live-action scene in which elements, too expensive to build,

are needed. The left image below shows the plate of the cargo bay set,

filmed from Kirk's point of view as he enters the Enterprise. What Andrew

Probert was required to do was to get a frame of plate film and have it

printed at a pre-determined size. A part of this frim, required for the

live-action elements, would be cut out and pasted to a piece of illustration

board. The remaining blank board, intended to be the matte, would then be

painted around that piece, blending the two together.

Following a discussion with special

effects director Donald Trumbull on how the cargo pods would get in and out

of the cargo deck, Andrew Probert draw an elevation sketch of the Enterprise

engineering section. He presented the sketch to Trumbull as a solution to

that problem, and Trumbull approved.

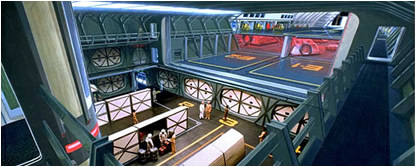

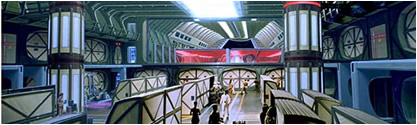

The next step was for Andrew Probert to

get some plate footage, and start his matte renderings. A matte rendering is

simply a painting that illustrates how the final scene might look like. Once

that image is approved by the director and the producers, it is sent to the

matte department, so that the matte painter can made the actual working

matte.

What Probert proposed was that the

landing bay and cargo bay be connected, allowing the easy passage of cargo

trains. The landing bay doors remain open, but atmospheric integrity is

maintained with a force field. The idea is that shuttles would normally take

off from and land in the landing bay. They then could be lowered to the

hanger bay level, or lowered

another level to shuttle maintenance. A multi-panelled

two-story door, between the elevators and cargo bay, has been opened to the

sides allowing the transfer of cargo.

From a lower

angle, one can see the secondary rollaway decks

protruding somewhat from the sides of the bay. In their current retracted

position, they serve as a walkway at that level. The

idea here was that, once the main deck was filled with free-standing pods,

the second deck would slide together, doubling the available deck space. Not

an ideal solution, but one that worked with the plate footage that had

already been shot. The side doors, with red stripe

white lettering, would lead to a section of lifeboat stations located along

each side of the outer hull.

Throughout most of the filming of The Motion Picture, a

final ending had yet to be developed. Andrew Probert provided the

producers with his own script suggestions for a visually dramatic conclusion,

and storyboarded the key event. The possibility of the original Enterprise

undergoing a saucer seperation was first mentioned in the original series

episode "The Apple", but it was not until the pilot episode of The Next

Generation that the maneuver was finally depicted.

Eventually it was decided the climax of the movie would be

the walk to the heart of V'Ger, and the eventual merging of the Ilia-probe

and commander Decker. The walk

to V'Ger was to convey a sense of the extraordinary and fantastic by

using the new visual effects to complement the original film rather than

overwhelm it.

All material may be reproduced

under the Terms of Usage outlined in the legal

disclaimer. Simply stated, this means appropriate credit must be given in the form of a hyperlink.

For any content used by courtesy of a third party,

this third party is to be credited. |

|

|

|

![]()