| |

|

|

After several attempts to bring Star

Trek to the screen, in 1977 Paramount decided to produce a second television

series, appropriately titled Star Trek: Phase II. Barry Diller, at the

time president of Paramount, had grown concerned by the direction in which

Star Trek had been taken in the latest movie script - Planet of the

Titans, by Chris Bryant and Allan Scott. After the film had been

canceled in preproduction, Diller had gone to Gene Roddenberry and suggested

it was time to take Star Trek back to its original context - a television

series.

Though Paramount was at fisrt reluctant

to put aside the development work that had been undertaken for the canceled

movie, Roddenberry wanted to reunite as many members of his original

production team as possible and start the design process again. These

paintings were part of that process, giving us a glimpse of one possible

Star Trek that never was.

Ralph McQuarrie is best known to the public for his stunning

production designs for the Star Wars films. His imagination helped guide the

final appearance of Darth Vader and his storm troopers, and he also created

many of the matte paintings of planets and satellites that appeared in the

film. After Star Wars wrapped in 1977, McQuarrie was invited to England to

work under Ken Adam to help develop the designs for a new Star Trek movie,

ultimately abandoned to make way for STar Trek: Phase II, the television

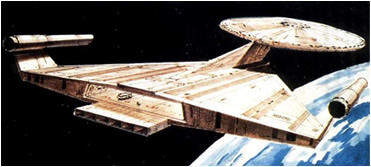

series. Their Enterprise-design,

however, was abandoned, and Roddenberry asked Matthew Jefferies to update

the famous starship to reflect the refit that would be part of the series'

backstory. Jefferies' redesign changed the engine nacelles from tubes to

thun, flat-sided modules, and tapered their supports. He also added the

distinctive photon torpedo ports on the saucer connector.

Unlike the first redesign of the Enterprise, Jefferies' new

version was built this time by Don Loos, who had built the original ship for

the original series. But when Paramount abandoned its plans to create a

fourth television network and subsequently transformed the second Star Trek

series into the first movie, that Enterprise was packed away as movie

director Robert Wise brought in a new art director - Harold Michaelson - who

started a second redesign of the ship, essentially keeping Jefferies' new

lines, while adding the extensive detail that was necessary for a

motion-picture miniature.

Mike Minor, who had provided many of the wall paintings seen

in the original series, as well as having designed the Melkotian from "Spectre

of the Gun", and the Tholian web, part of the Emmy-Award-winning visual

effects in the episode of the same name, also returned to contribute to the

updating and redesign of the series. Jim Rugg, another veteran from the

first season of the original Star Trek, was brought back to be in charge of

special effects. Mike Minor's

initial designs for the new Star Trek series are clearly the evolutionary

step between the original series and The Motion Picture. The bridge-wall

control modules survived almost intact to The Motion Picture (note the

holographic starmap projector in front of the captain's chair), while the

transporter room is essentially a redress of the original set with a more

streamlined console and new all displays. The recreation room concepts, also

by Mike Minor, show several crewmembers playing

some kind of anti-gravitational game, and some engaging in intimate

conversation.

As early as the original series' third season, Gene

Roddenberry had spoken of making a Star Trek motion picture. At the 1968

World Science Fiction Convention held over the Labor Day weekend in Oakland,

California, he drew enthousiastic applause when he told a rapt audience his

plans for filming a prequel to the series, telling the story of how Kirk and

his crew had met at Starfleet Academy. For that weekend at least, Star Trek

was on a roll. But the Tuesday after Labor Day, the real world intruded and

kept the opening of the first Star Trek movie at bay for more than a decade.

Yet the idea of a movie continued as Roddenberry's dream

throughout that decade, sometimes coming tantalizingly close to becoming

reality, only to be snatched away by the capriciousness of Hollywood deal

making. In the spring of 1975, Paramount entered into a deal with

Roddenberry in which he would write the script for a low-budget Star Trek

feature, tentatively to cost between two to three million dollars.

When Roddenberry delivered his script - The God Thing

- in August on that year, Barry Diller, the president of Paramount, rejected

it, but asked Roddenberry to write another. At the same time, the studio

also invited other writers, cinluding Harlan Ellison, Robert Silverberg and

Star Trek veteran John D.F. Black, to try their hand at pitching a suitable

story. In the meantime, Gene Roddenberry went backt to work on a second

script, this time with cowriter Jon Povill. Once again, Paramount passed.

But despite the trouble they were having finding a script, the studio's

interest in making a Star Trek movie continued to grow.

All material may be reproduced

under the Terms of Usage outlined in the legal

disclaimer. Simply stated, this means appropriate credit must be given in the form of a hyperlink.

For any content used by courtesy of a third party,

this third party is to be credited. |

|

|

|

![]()