| |

|

|

Moscow architecture from the 1930s

to the early 1950s undoubtedly occupies a central place in domestic

construction of the socialist epoch. Its specific nature and scope is the

most outstanding illustration of the socialist Utopia in architecture. This

period saw the work of the greatest Soviet architects; B. Icfan, A. Schusev,

I. Zholtovsky, the Vesnin brothers, I. Fomin, L. Rudnev, I. Golosov, V.

Schuko. Among the far-reaching projections of the first Stalinist

"five year plans", the 1935 general plan for the

reconstruction of Moscow overshadowed all others.

According to this plan, Moscow was

to become, in the shortest possible time, the showpiece capital of the

world's first socialist state. The ceneral plan

envisaged the development of the city as a unified system of highways,

squares and embankments with unique buildings, embodying the ideas and

achievements of socialism. This plan contained a number of major flaws,

especially in connection with the preservation of the historical heritage of

the city. The specific nature of the architectural process of this period

was determined wholly by ambitious government schemes.

In order to realize them, extensive

architectural contests were held and architects of diverse orientations and

schools of thought were invited to tender their projects. The competitions

for the projects of the Palace of Soviets (1931-1933) and for the building

of the People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry (1934) were particularly

noteworthy in scope and results. Although, ultimately, neither of these

projects was realised, the plans submitted by the participants had a

noticeable influence on the development of Moscow, and many of the entries

have earned a place in this century's repository of project planning.

At the time, this style of

architecture, like its contemporary literature and Soviet depictive art,

were proclaimed to be an exemplary implementation of the "most progressive"

artistic method of "socialist realism". Considered today, it is clear that

the best examples of this architecture, most of which never got beyond the

drawing board, are more profound and interesting than the ideological norms

within the constraints of which they were devised. Behind many grandiose

projects one may often discern the desires of those endowed with power to

affirm the greatness of this or that historical epoch. May the unrealised

plans of these monumental buildings serve as a reminder that it is right and

proper to build innovatively without destroying the historically valuable

past. That which history has given us, both good and bad, is our undeniable

heritage, and we must accept it as it is. Yet we should not forget the

lessons history has taught us, for upon this hinges the future of Russia.

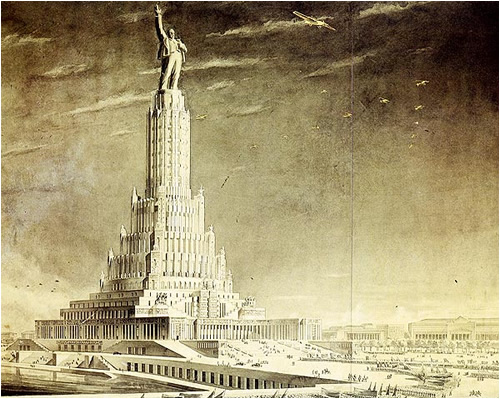

Palace of Soviets. O.Iofan, O.Gelfreikh, V.Schuko.

Sculptor S.Merkulov. A Version of the approved project. 1934

The

competition for the Palace of Soviets in Moscow was one of the most

extensive and impressive of this century. The idea of constructing a

building which could be a symbol of the "imminent triumph of communism" in

the capital of the world's first state of workers and peasants was mooted in

the 1920s. The chosen location was the site of the demolished Church of

Christ the Saviour. The competition was launched in 1931, and carried out in

stages. Overall, 160 entries were submitted, including 24 from foreign

participants. The definitive turn of Soviet architecture toward the heritage

of the past had emerged clearly by that time, and was the key factor in the

choice of winners.

The top awards went to architects G.

Hamilton from the United States, Ivan Sholtovsky and Boris Iofan (who also

designed the Soviet pavilion at the 1937 world exhibition) from Russia.

Iofan designed the winning plan with architects Vladimir Gefreikh and

Vladimir Shchuko.

Atop of the Place of Soviets would

be placed a colossal statue of Lenin. The statue alone would already be

twice as high as the Statue of Liberty in New York. The entire building

would be 495 metres high.

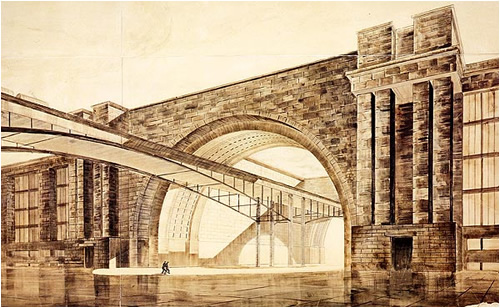

The Рalace of Technology. А.Samoylov, B.Yefomovich.

1933

A competition for a design for the

Palace of Technology was announced in 1933. The project called for a complex

of scientific and technical institutions, it was to be in the the capital

city of a country which was being actively industrialised by a central

administration called upon to "arm the masses with the achievements of

Soviet industrial technology, agriculture, transport and communications". A

site on the banks of the Moskva river was selected as the location of this

Palace. The industrial resolution selected by A. Samoylov and B. Yefimovich

was not a tribute to a constructivisim which was receding into the past, but

rather an illustration of the "technocratic" character of the subject. The

Palace of Technology was never built.

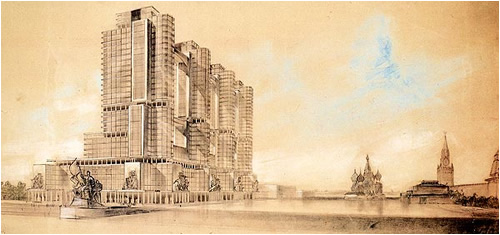

The building of the People's Соmmissariat of Heavy

Industry, A. Vesoin, V, Vesnin, S. Lyaschenko. 1934

A competition for the design of a

building to house the People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry (Narkomtyazhprom)

on Red Square was announced in 1934. The construction of this grandiose

complex of 110,000 m3 on an area of four

hectares would have resulted in a radical reconstruction of Red Square and

adjacent streets and squares of Kitai-Gorod. Twelve entries were submitted

for the first stage of the competition. The impressive plans drawn up by the

brothers A. and V. Vesnin --

leaders of the constructivist movement --

were not noted by the jury, along with a number of other entries,

although the submissions included some of the most interesting architectural

ideas and projections of this century. The building of the People's

Commissariat of Heavy Industry was never realised.

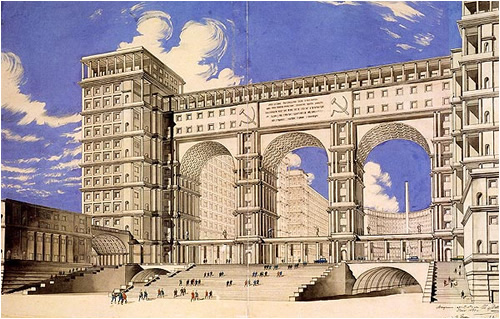

The building of the People's Commissariat of Нeavy

Industry. I.Fomin, P.Abrosimov, M.Minkus. 1934

I.Fomin was a leading representative

of the St. Petersburg neo-classical Russian school of architecture, and had

attained prominence before the revolution. Even in the 1920s, a period

dominated by constructivism, Fomin managed to remain faithful to the

principles of classical architecture and even devised a so-called

"proletarian-order" expressed thus: "the two basic verticals of the main

facade create an aperture which provides a clear view of the mausoleum.

Along Sverdlov Square, the construction finishes with a butt-end. We have

selected the silhouette technique as the solution. The butt-end will be

divided by a very ornate arch to blend with the character of the Square's

old architecture. The building is planned as a closed circle. As the

construction is a closed one, we did not wish to go above 12-13 floors, with

only the tower reaching a height of 24 floors" - extract

from annotations to the project.

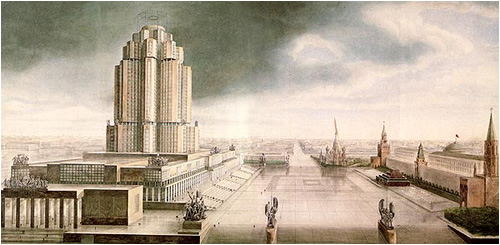

The building of the People's Commissariat of Нeavy

Industry. А.Vesnin, V.Vesnin, S.Lyaschenko. Version. 1934

"...Four towers, up to a height of

160 metres, on a stуlоbate which harmonizes with the Kremlin wall. A

rhythmical construction, expressed in four vertical elements and the

colonnade of the stylobate, creating a visual extension, essential to the

longitudinal framing of the Square and responding to the Kremlin wall. The

vertical divisions correspond to the four divisions of the Kremlin tower and

are necessary for the inclusion of the building into the overall ensemble.

The project envisages a single vestibule the length of Red Square"

- extract from annotations to the project.

The Aeroflot Building. D.Chechulin. 1934

In 1934, the attention of the whole

world was focused on the fate of the crewmen of the ice-breaker "Chelyuskin",

who were adrift on an ice-floe after the ship went down in the Sea of

Chukotsk. In the summer of the same year Moscow greeted the courageous

survivors and the pilots who had rescued them, and who were the first to be

granted the "Hero of the Soviet Union" award. The new traditions of

socialist life demanded the perpetuation of the memory of this outstanding

feat in monumental form. The "Aeroflot" building, which was to be erected on

the square beside the Byelorussky railway station, was planned by architect

D.Chechulin as a monument to the glory of Soviet aviation. Hence the

sharp-silhouette, "aerodynamic" form of the tall building and the sculpted

figures of the heroic airmen A.Lyapidevsky, S.Levanevsky, V.Mоlоkоv,

N.Kamanin, M.Slepnev, M.Vodopyanov, I.Doronin, crowning seven openwork

arches, perpendicular to the main facade and comprising a distinctive

portal. I.Shadr, the sculptor of the airmen's figures, took part in the

project's design. The project was never realised in its original design or

intention. Almost half a century later, the general ideas of the project

were incorporated into the complex housing the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR

on thе Кrasnоргеsnenskауа Еmbankment (nоwadауs: Gоvernment

Ноuse).

House of Books (Dом Knigi). I.Golosov, P.Antonov,

A.Zhuravlev. 1934

The plan of the House of Books is

typical of early 1930s perceptions of a building as an architectural mоnument.

A trapezоid tall silhouette, simplified architectural forms and an abundance

of sculptures on all parts of the building. Architect I.Golosov achieved

prominence in the constructivist movement in the 1920s (the "textbook" Zuyev

Club was his project), and in subsequent years he found interesting

solutions in the spirit of the new Soviet classicism. He submitted original

projects to the competitions for the House of Soviets and the building of

the People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry. Golosov's work is distinguished

by features which are designated "symbolic romanticism". "The architect must

not be bound by style in the old, historical sense of that word, he himself

must be a creator of style... То this end, it is essential to set guidelines

which facilitate the optimum realisation by the builder of each individual

project... One must establish only absolute tenets, those which are

inevitable, true and unchanging. There are many such, and these tenets, as

vehicles of absolute values, are equally applicable to classical and

contemporary architecture" - I.Golosov,

from his lecture New Paths in Architecture.

Residental building on Vosstaniya Square.

V.Oltarzhevsky, I.Kuznetsov. 1947

Architects V.Oltarzhevsky and

A.Mordvinov worked together on the plans of the high-rise building of the

Ukraina hotel on Kutuzovsky Prospekt (1954). V.Oltarzhevsky devoted much

time to architectural theory and methods of constructing tall buildings. In

1953 he published a book, High-rise Construction in Moscow, in which

he tried to establish links between this type of architecture and the

traditions of Russian building. He was particularly

interested in the construction and versatility of methods of technically

equipping the "high-rises". Oltarzhevsky's project was never realised. The

tall building on Vosstaniya Square was constructed to a plan by the

architects H. Posokhin and A. Midoyants (1953).

Tall building in Zaryadye. View from the Red Square.

D.Chechulin. 1948

In 1947, the Soviet government

adopted a resolution concerning the construction of high-rise buildings in

Moscow. By the early 1950s, tall buildings had been erected on Lenin Hills

(Moscow State University), the Foreign Ministry on Smolenskaya Square, an

administrative building on Lermontovskaya Square, the "Leningradskaya" and "Ukraina"

hotels on Komsomolskaya Square and Kutuzovsky Prospekt and residential

buildings on Kotelnicheskaya Embankment and Vosstaniya Square. Only the

construction of a 32-floor administrative building in Zaryadye, which was

envisaged as one of the salient features of the silhouette of the central

city skyline, was not completed. Work on it was stopped after the 1955

resolution of the Central Committee, which condemned "excesses and

over-ornamentation in architecture" and signalled a new era in Soviet

architecture. The work which had been done was dismantled, and the hotel "Rossiya"

(also planned by D.Chechulin) was built on the foundations in 1967.

This information is republished here at

the courtesy of The Architecture of Moscow

from the 1930s to the early 1950s: unrealised

projects.

Museum of Architecture, Moscow. |

|

|

|

![]()