|

Following the Baroque

with its fantastic decorations and spectacular effects, the need for harmony

and elegance arose under artists, especially under European architects. The

classic antiquity was again taken as model. During the Age of Enlightenment,

high value was attached to archaeological reconstruction and rational

approach. The style which preceded neo-classicism first arose in the United

Kingdom, and was inspired by the publications of the Italian architect

Andrea Palladio, who was strongly inspired by classical architecture in the

16th century. His conceptions played a major role in American architecture

of the 18th and 19th century. Well-known examples are the Capitol, the White

House, and the university of Virginia, designed by later president Thomas

Jefferson.

University

of Virginia: Architect and

statesman Thomas Jefferson was the third president (1801-1809) of the United

States of America. Together with Latrobe, he designed the University of

Virginia in Charlottesville. Construction began in 1822, and the campus was

completed in 1826. The Rotunda dominates the university grounds. Threw a

simple pronaos, one enters the villa with its three oval rooms and

its beautiful, round library.

The Rotunda

was designed to be the architectural and intellectual heart of his academic

village. Jefferson modelled the Rotunda after the Pantheon in Rome, reducing

the measurements so that the building would not draft the neighbouring

Pavilions.

The Lawn at

the university extends from the Rotunda at the north end to Cabell Hall at

the south. It is framed on either side by the Pavilions, which house

distinguished faculty members, and living quarters for student leaders.

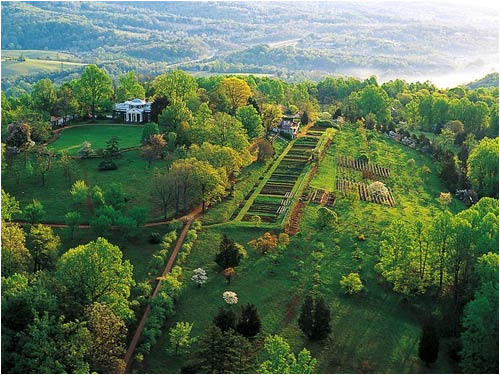

Monticello: Thomas Jefferson

spent most of his life designing and redesigning his house, Monticello,

which was constructed over a period of fourty years. He said, "architecture

is my delight, and putting up, and pulling down, one of my favourite

amusements."

Jefferson inherited sizable

property in Albemarble Country, Virginia, from his father, Peter Jefferson,

who along with Joshue Fry created the most accurate map of Virginia of their

time. In May 1768, the 25 year old Thomas Jefferson began to level the

already gentle top of a 987 foot high mountain, where he intended to build

his home. He called it Monticello, which means "little mountain" in old

Italian.

The first Monticello: The

self-taught architect designed Monticello after antient and Renaissance

models, and in particular after the work of Italian architect Andrea

Palladio. In location - a frontier mountaintop - and in design - a

Renaissance villa - intentionally it was a far cry from the other American

homes of its day. Commenting on buildings in Williamsburg, Virginia,

Jefferson wrote, "the genius of architecture seems to have shed its

maledictions over this land."

Work on Monticello was largely

completed in 1782: the first floor of the house featured a bedroom, parlor,

drawing room, and dining room. As the house neared completion, however,

Jefferson's wife died, leaving him, as he wrote, with "a blank which I had

not the spirits to fill up."

In 1784, Jefferson was appointed to

diplomatic service in France. While there, he was a keen observer of

architecture, writing that he was "violently smitten with the hotel de Salm"

in Paris, and noting that the Maison Carrée at Nîmes was "the best morsel of

ancient architecture now remaining." Both buildings influenced Jefferson's

later work: the Maison Carrée became a model for his plans for the Virginia

State Capitol in Richmond, and the Hôtel de Salm strongly influenced his

redesign of Monticello.

As early as 1790, Jefferson began

planning revisions for his Albemarble Country home, based in part on what he

had observed in France. In 1796, walls of the original home were knocked

down to make room for an expansion that would essentially double the

floorplan of the house. The new plan called for a hallway connecting the

older rooms to a new set of rooms on the east. The second Monticello was

largely completed in 1809, the year Jefferson retired from Presidency.

The second Monticello: Among

the many French elements that Jefferson incorporated into the second

Monticello, the most dramatic was the dome placed over the already-existing

Parlor, making it the first American home with such a feature. He crafted

the building to give the appearance - as he had seen at the Hôtel de Salm -

that the three-story building was only one story tall. To achieve this

effect, windows in the second-story bedroom are on the floor level, so that

from the outside, they appear to be an extension of the first-floor windows.

On the third floor, light is provided by skylights invisible from the ground.

Alcove beds and indoor privies are two more French features incorporated

into Monticello.

Jefferson's revisions from the home

called for even smaller stairways than he had used in the original design.

Two steeps and narrow stairways, measuring only twenty-four inches wide,

provided access to the upper bedrooms. These stairways widen to thirty

inches as they descend to the basement level, thus affording more space for

tasks such as bringing food from the kitchen to the dining room. Jefferson

believed that small stairways saved both money and "space that would make a

good room in every story."

"Essay in architecture":

Jefferson called Monticello his "essay in architecture," and construction

continued on the mountaintop well into his retirement. In 1809 - fourty

years after work began on Monticello - his workers completed the

basement-level dependencies, such as the kitchen, smokehouse, and storage

rooms. The final product is a unique blend of beauty and function that

combines the best elements of the ancient and old worlds with a fresh

American perspective. In 1782, the marquis de Chastellux visited the "first"

Monticello and wrote a brief description of it for his Travels in

North-America.

"My object in giving these details

is not to describe the house, but to prove that it resembles none of the

others seen in this country; so that it may be said that Mr. Jefferson is

the first American who has consulted the Fine Arts to know how he should

shelter himself from the weather."

|

![]()