THE GATEHOUSE

THE GATEHOUSE

In steampunk as well as dieselpunk, we tend to exaggerate history. Where by the turn-of-the-century, airships gradually began to enter service, in steampunk, by this time, the skies are congested with dirigibles. And where Nazi scientists performed the most dreadful human experiments, in dieselpunk, their work produces frightening creatures, half-man, half-machine, striking terror into the hearts of Allied soldiers.

In terms of aesthetic, this exaggeration is more subtle, though equally significant. We augment Victorian style with design and technology the Victorians themselves perceived as futuristic in period Scientific Romances and Voyages Extraordinaires. Similarly, dieselpunk exploits the adventure and detective stories serialized in pulp magazines throughout its era, as well as the depictions of the future published in magazines as Popular Science and Modern Mechanix.

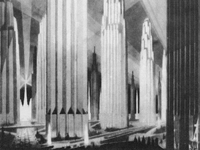

Though the visions of many forward-looking artists are now vividly manipulated to create a dieselpunk aesthetic, when it comes to architecture, one name stands out in particular. This American delineator mastered the medium of shadow and light, molding form in a way that truly captured the spirit of place and being. Rather than designing buildings of his own, he specialized in creating architectural renderings which served either to sell or promote a project.

Hugh Ferriss’s drawings were thus frequently destined for shows and advertisements and as a result, he acquired a reputation and found himself to be highly sought after.

By the advent of the Roaring Twenties, Ferriss had begun to develop his own style, typically presenting the building being advanced at night, lit up by spotlights, or in the fog, as if photographed with a soft focus. The shadows cast by and upon the building became almost as important as the revealed surfaces. He had somehow managed to develop a style that would elicit emotional responses from the viewer. The appeal of his work endured for decades to be eventually incorporated in the dieselpunk aesthetic. Indeed, Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow-maker Kevin Conran particularly credited his drawings as an influence upon the look of the film, in which we grasp a New York City notably similar to the visions of Ferriss.

The building styles of the 1920s and 1930s are an influence in more general terms also. The emergence of the skyscraper, along with the introduction of automobiles and aeroplanes, with petroleum replacing steam as the primary source of energy, define the urban dieselpunk world in which its pulp-inspired, neo-noir tales are set.

New York City was very much the center of modern architecture and modern art in general ever since the Roaring Twenties. Art Deco was one of the most popular design movements of the era, which, because of its lack of political and philosophical roots or intentions, suits the technocratic character of dieselpunk perfectly. The style was at the time considered to be elegant, functional, and modern—in other words, the style of the future.

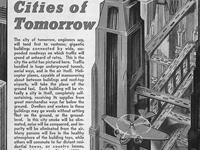

That future was to be a bright one. Even as World War II broke out in Europe, Amazing Stories ran a prediction of the future metropolis, which, it believed, would “tend to vastness.” The magazine imagined “gigantic buildings connected by wide, suspended roadways on which traffic will speed at unheard of rates.” Further traffic would be “handled in huge underground tunnels, aerial ways, and in the air itself. Helicopter planes, capable of maneuvering about between buildings and roof-top airports, will take the place of the ground taxi.” This was no strange prediction, for earlier futurists had already imagined the skies over New York to be swarming with dirigibles in the future.

“Each building will be virtually a city in itself,” Amazing Stories goes on to write, “completely self-sustaining, receiving its supplies from great merchandise ways far below the ground. Dwellers and workers in these buildings may go weeks without setting foot on the ground, or the ground-level.” No further mention is conveniently made of the sad proletarians who will dwell within these monoliths for weeks without sunlight. “In this city smoke will be eliminated, noise will be conquered, and impurity will be eliminated from the air. Many persons will live in the healthy atmosphere of the building tops, while others will commute to far distant residential towns, or country homes.”

New York City is not surprisingly the center stage of many dieselpunk works of fiction. The quintessential dieselpunk film, Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, gave us a glimpse of a skyscraper city beautifully lit up at night by enormous floodlights. Frank Miller called the setting of the 2008 film The Spirit, “mythic New York” while Batman writer and editor Dennis O’Neil compared Gotham City in the afterword to the novel, Batman: Knightfall (1994) to, “Manhattan below Fourteenth Street at eleven minutes past midnight on the coldest night in November.”

Left artwork above by Stephane Belin. Click to hide this item.

Although Art Deco fell out of vogue in the 1940s, it is still incorporated in contemporary architecture and media to evoke a “classic retro” look. In Tim Burton’s Batman (1989), as well as in Batman: The Animated Series, Art Deco is fused with a deliberate darkness to create a variant style sometimes referred to as “Dark Deco”. Similar elements can be seen in both the film adaption of Sin City (2005) and the movie Perfect Creature (2006) to make for a more dystopian look, reminiscent of the “metropolitan drama” that speaks from Hugh Ferriss’ drawings.

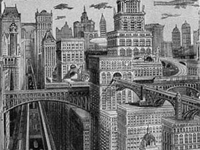

This illustration by Mikko Kinnunen depicts just one of the many visions that the hometown of Batman has known. Gotham’s atmosphere took on a lighter tone in the comics of the post-World War II years, as did the Batman stories themselves. However by the 1970s the city, and the stories, became grittier. Today, Gotham is typically depicted as a dark and foreboding metropolis rife with crime, grime, corruption and a deep-seated sense of urban decay.

“The Dark Knight stands watch over the city he calls home,” amid towers shooting skywards that glisten in the humid night. Lights that sparkle in twilight seem to wink from across the depth that blazes in white fury beneath. The towers with their fast-fadings lights are like obelisks of tranquility rising from incomprehensible babel below. This is Gotham, “a city run by crime, with a riot of architectural styles. An essay in ugliness. As if hell erupted through the pavement and kept on going,” according to Anton Furst who designed the noirish nightmare version of Tim Burton’s Batman (1989).

Different artists have depicted Gotham City in different ways. Oftentimes they based their interpretations on various real architectural styles with exaggerated characters, such as the massively multi-tiered flying buttresses on Gothic cathedrals. Gargantuan Art Deco and Art Nouveau statuary could be seen in Tim Burton’s films while Joel Schumacher exploited elements of cyberpunk.

Artwork by DUSSO and Leif Heanzo, among others. Click to hide this item.

In the late-nineteenth century, the Chicago School pioneered steel-frame construction and the use of plate glass, building some of the first modern skyscrapers. The city brought about a neo-classical revival with its “White City” built for the 1893 World’s Exposition yet subsequently paved the way for Art Deco with for example this Palmolive Building which was completed in 1929 and served as headquarters of Playboy between 1965 and 1989.

Chicago’s cityscape is a dazzling conglomeration of many different buildings styles. Some of the earliest skyscrapers of the Chicago School still stand proudly erect although overshadowed by the monoliths of modernism. In between we find streets lit up in blazing fury at night. Looking north from the Chicago Board of Trade Observatory, we spot the LaSalle-Wacker Building to the left, its beacon radiating in all directions. To the right stands the Chicago Temple Building, completed in 1924 and still the tallest church in the world. The Chicago Board of Trade Building itself (photograph by Paul Saini) was used by Christopher Nolan in his Batman films as the headquarters of fictional Wayne Enterprises.

Click to hide this item.

Dieselpunk also borrows stylistically from the immediate post-World War II years, notes Piecraft. “The dieselpunk world is a post-atomic dystopian [one],” he writes, “that is still stuck in the 1950s [...] and is usually cast in the future capitalist-run world that relies on the nuclear values of an isolationist America.” George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and even Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged are novels which may be considered as thematic influences upon this kind of dieselpunk fiction.

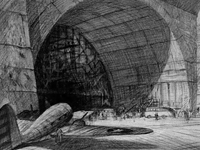

In terms of architecture, this implies the integration of Modernism in the vein of Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, however such is typically restricted to futuristic proposals never really built. In dieselpunk, ambitious urban planning and grand building proposals do come true, although because of alternate histories in which the war is still being fought as a prolonged Cold War, it are not so much the skyscrapers of the International Style, rather the monumental architectures of Nazi-Germany and the Soviet Union which define the dieselpunk landscape of the 1940s and 1950s.

Stalinist Architecture originated with Boris Iofan’s 1933 draft for the “Palace of Soviets” and remained popular until 1955 when Nikita Khruschev condemned the excesses of the past decades. Not a building style per se, characterized by a distinct appearance, it describes instead an architecture that resulted from the manner in which the Soviet State communicated with the masses through construction, considering them an expression of state power.

The combination of striking parade monumentalism, patriotic art decoration, and traditional motifs has become one of the most vivid examples of the Soviet contribution to architecture.

Throughout the 1940s and ’50s, the Soviet magazine, Znanie Sila often presented its readership with covers that depicted how the Communist leadership wished its people to think of their country—prosperous and powerful and a beacon of patriotic pride. These covers showed the great accomplishments of the Soviet nation, ranging from its pioneering space program to the grand structures that dominated the Moscow skyline. Most of the towers and monuments depicted were actually built, however the modern cars and helicopters encircling them must have seemed science-fiction to most of the Soviet people at the time.

Click to hide this item.

Sketch of the Helsinki Central railway station (detail).

Blade Runner tribute by FBRCCN.

For more architecture of interest, visit our SMOKING LOUNGE.